With inflation soaring after the pandemic, and still five times the Bank of England’s target in the UK, can unruly inflation be defeated and, if so, at what cost?

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, economies across the globe witnessed inflation rising to its highest levels in decades and central banks trying their best to tame it.

In the US and eurozone, as we approach the second half of 2023 inflation is cooling in line with economist’s expectations. Although still well above central banks’ 2% target, US inflation slowed to 5% in March. However, in the UK inflation remains at 10.1% as of March, and a 45-year high of 19% inflation in food.

Why did inflation rise after the pandemic?

The economic impact of lockdowns across the globe was unprecedented. GDP in the USA in Q2 of 2020 fell by 30% and in the UK by 21%. Central banks and governments had the task of finding ways to increase spending to boost the economy. They did this by pumping money into the economy, in particular via zero or even negative interest rates, and quantitative easing (QE). Quantitative easing is essentially a modern way for banks to print more money.

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) reduced interest rates (which had, in any case, not been raised much following the global financial crisis) to 0.25% in March 2021, and the ECB and US Federal Reserve lowered theirs even more.

Governments also spent money. Both the US and UK introduced “Build Back Better” plans. The US, via the “American Rescue Plan”, pumped trillions of dollars into the economy including simply sending cheques worth $1,400-$2,000 to economically disadvantaged working families.

Meanwhile plenty of people were still working, but physically prevented from spending money. According to the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS), there was “forced saving” of £140bn during the pandemic.

When the pandemic lockdowns ended, all that money, combined with the economic stimulus, led to large scale spending. Meanwhile, supply chains took longer to recover. China’s “zero-Covid” policy continued to disrupt supply long after Western buyers returned to the shops.

When supply is unable to meet demand the inevitable result is inflation. Moreover, there is some evidence of suppliers simply raising prices because they could. After all, many businesses lost a lot of money in the pandemic and had ground to recover.

Another inflationary pressure has been a tight labour market. In the UK, some 500,000 older adults left the workforce, either due to ill-health in the wake of Covid-19 or to take early retirement having saved money. To this you can – arguably – add Brexit effects, with many EU workers leaving, pushing up the cost of harvesting agricultural products, for example.

Surging oil prices

Then in February 2022, when inflation was already rising, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered gas and oil prices to surge. The ONS reported that “electricity prices in the UK rose by 66.7% and gas prices by 129.4% in the 12 months to March 2023, and were some of the main drivers of the annual inflation rate”.

Since every product and even most services require some sort of energy, inevitably prices rose across the economy.

UK, EUR, USA: who has the highest inflation?

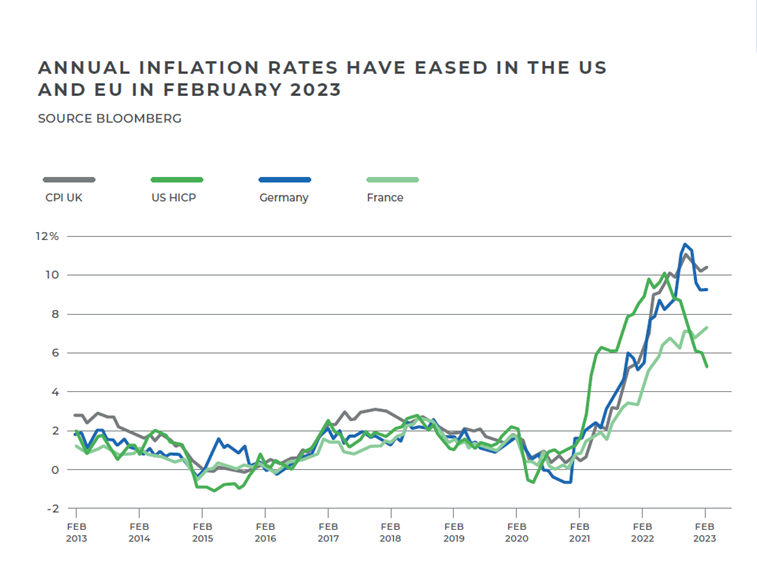

Between our three key currency zones, inflation is currently highest in the UK at 10.1%. Spanish and French inflation is at 3.3% and 5.7% respectively, while Germany’s rate is at 7.4%. The euro area as a whole has 6.9% inflation while in the USA it is down to 5%.

Above is a comparison of UK, US, French and German inflation rates. UK inflation climbed into double digits in summer 2022 and has stayed there, peaking at 11.1% in October but still only slightly less than that now, a full five times higher than the BoE’s target.

How high inflation impacts the economy

High inflation has been problematic for the UK economy.

Rising prices and living costs have led to a number of strikes across key sectors, which has in turn negatively impacted the economy. According to the ONS monthly GDP flatlined in February of 2023, not least because teachers, civil servants and medical staff, among others, were on strike.

Rising prices are also a stress on households, discouraging spending. The UK’s consumer confidence readings during the past few months of high inflation are even worse (as low as -49) than during the darkest days of the pandemic.

How are central banks responding to inflation?

Central banks have an inflation target of 2%, to maintain economic stability. Deflation is never good for an economy, hence the safe margin of a 2% target. Depending on whether inflation is too high or too low the BoE can raise or lower interest rates. This is known as monetary policy, and the Bank of England’s nine-member interest rate setting panel is the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

A tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates, aka quantitative tightening, or QT) should bring inflation down, and vice versa. How long a change in interest rates takes to work through the system is a moot point. The conventional wisdom is at least 18 months. However, there is some evidence that it can take just a few weeks for some effects to come through – for example on the property market.

With UK inflation sitting at 10.4% just before its March meeting, the MPC voted 7/2 to raise interest rates by 25 basis points to 4.25%.

In the long term, the Bank of England’s analysts forecast that the measures it has already taken will cut inflation to 5% by the end of 2023 and 1.5% by Q4 of 2024. Hence it may have to lower interest rates later in the year, or early 2024, to raise inflation to the 2% target.

Read more about how the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank are also responding to high inflation in our latest Quarterly Forecast.

What does it all mean for exchange rates?

The relationship between inflation and currency exchange rates is straightforward but flows via interest rates. These influence the flow of capital between countries: when interest rates rise it becomes more attractive for foreign investors to invest in a country, as they can earn a higher return on their investment. This leads to an increase in demand for pounds and a rise in their value.

Hence the monthly (more or less) interest rate announcements from the MPC and its equivalent in the US Federal Reserve (the FOMC) and the ECB are among the most influential factors governing exchange rates. Indeed, so are individual comments from members of the panels, who soon become known as ‘hawkish’ or dovish’.

The strength and subsequent weakness of the dollar in the past year has been almost entirely down to interest rate expectations.

How Smart can help you navigate the risk

Inflation in the UK remains high by international standards, whether you blame Brexit or other factors. Individual members of the MPC, including Andrew Bailey, are resolute on bringing inflation to heel by 2024.

However, the prevailing view is there will be another interest rate hike at the next MPC meeting on 11th May, of 25 basis points, taking the UK Bank Rate to 4.50%.

We cannot be certain that things will go to plan. February’s unexpected rise in inflation, for example, is a warning.

Our Quarterly Forecast is a useful tool for gaining expert knowledge on currency markets and the events that move them. It includes bank predictions for each quarter of 2023 and up to spring 2024. Download our Quarterly Forecast here.

In addition to reading our Quarterly Forecast, we also advise having a risk management approach to exchange rates. Get in touch with us today on 02078980541. We will be delighted to help.