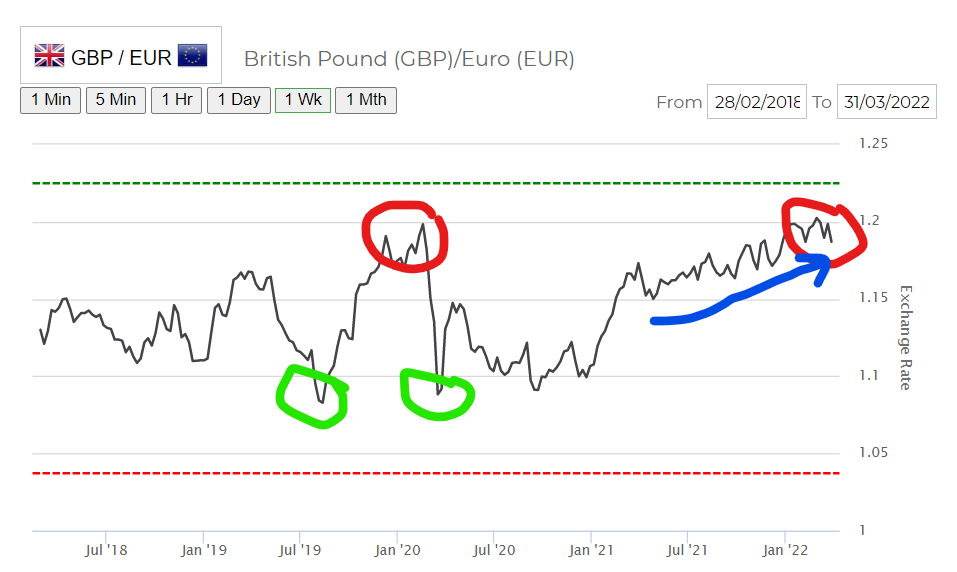

The pound has slipped in recent days, after failing to stay above the €1.20 resistance level for more than a few days at a time. Will it ever regain its pre-referendum levels?

Several times since the start of 2022 the pound has reached over €1.20 against the euro. It’s the first time that GBP/EUR has been there for more than a day or two since before the 2016 referendum. Indeed on 7 March it reached close to €1.22, but only for one morning.

The last time it – briefly – reached €1.20 was in the two months after the 2019 election. Anyone who had been keeping track for several years – maybe planning a move abroad – might have hoped that it signalled the end of the Brexit melodrama and economic shock, and a return to business as usual. Perhaps with sterling back up to the pre-referendum levels of around €1.38, as it was in 2015.

Then the pandemic came along, with its likely outsized effect on the kind of service industries on which the UK relies (Markit Services PMI fell from 53 in February 2020 to 35 in March and 12 in April 2020). Little surprise that the pound suffered inordinately. It only recovered in early 2021 when it became obvious that the UK government had got its vaccine policy right and stolen a march on its EU and other economic rivals.

Was strength the anomaly?

Why has sterling not returned anywhere close to pre-referendum levels?

Firstly, there is an argument that 2015 was the anomaly. The average for GBP/EUR in the five years prior to the global financial crisis in 2008 was around €1.45, and in the five years after was €1.12 to €1.23.

January 2015 was the month that the far-left Syriza won the Greek election on a platform of refusal to cut spending to satisfy the EU, and Grexit became a strong possibility.

However, in May 2016, the month before Brexit, the Greek government passed a new austerity package, averting the eurozone’s crisis and the euro may well have strengthened over the long-term anyway.

October’s rogue algorithm

Although sterling weakened dramatically in the days after the referendum, losing 10% against the euro, it had stabilised by the late summer, albeit at a lower rate. Then, like a plummeting lift in a disaster movie that’s descent is temporarily held up by squealing brakes, it dropped another 5% against the euro in early October 2016, and to a 31-year low against USD. Why?

The answer is probably ‘algorithmic’ – or automatic – trading, whereby computers are entrusted/programmed to make trades automatically, based on pre-set instructions. So one theory is that when the French president was reported to have said he wanted tough Brexit negotiations, something clicked in a computer causing a sell-off of the pound.

Re-reading news reports of October 2016, it’s interesting with the benefit of hindsight to see the comments. The Head of Rates at UBS “forecasts sterling will hit $1.20 by the end of 2017” said BBC News. In fact it took not 15 months, but one month. The same expert predicted GBP/EUR to settle at parity – it has never come close. So much for experts.

Trends and resistance

A resistance level in currencies is where a strengthening currency consistently fails to break through a price band. It is not, generally, based on anything much more that traders’ sentiment and previous buyer behaviour. The opposite, a price level at which a currency generally fails to fall beyond, is a support level.

Since the referendum the key support level for GBP/EUR has been €1.10 (marked green) and the key resistance level €1.20, marked red. When the currency reaches close to that point the markets effectively have a serious rethink about whether they want to risk going any further.

To do so requires a fresh impetus; energy from a new source.

So, while the pound powered to €1.20 at the start of 2022 on the rise in interest rates and the risk to European business, that energy has been exhausted and nothing new has emerged to keep it moving upwards. In the meantime, sanctions on Russia and a risk-off mindset, keeping to safer havens in a crisis, prevented it going further.

The markets, now casting around for news that might be a risk to sterling, have easily found it in the Bank of England’s equivocation on interest rates (where one member of the nine-person committee voted against the rise), plus the governor Andrew Bailey’s comments on the risk of stagflation (low growth + high Inflation), plus the possibility that the Russian army has given up on capturing Kyiv.

Traders will also look at the shape of the graph to look for where a currency is likely to go next. Notice the long line of near unbroken growth since spring 2021 (blue line) powered by the recovery from the pandemic (with services PMI now around the 60 mark, from a low of 12) where arguably the government got it right again in ignoring the Omicron variant.

A rise of that length looks likely to be checked at some point, and it has.

Future shocks and black swans

So, in conclusion, since the referendum sterling has been trading between two support and resistance levels – €1.10 and €1.20 – with a rough average of €1.14.

Two ‘black swan’ events, the pandemic and Ukraine war – unforeseen at the time but logical with hindsight – have moved it between those levels but failed to break them.

No-one knows what lies around the corner. It could be an energy crisis, inflation truly getting out of control, a larger-scale war or even a Covid-19 variant that beats the vaccines. Brexit has not entirely been played out yet, with potential for the Northern Ireland protocols to cause a trade war. Politically, the next few years may see the end over a decade of Conservative-party led rule, and maybe the return of Donald Trump as 47th President.

Therefore the most sensible course of action will alway be to control what you can control.

At Smart we use a simple model for that decision: Budget, Risk, Solution.

First you work out how much you need for your plans – buying a property abroad, for example. That’s the budget element. Then you look at the potential risks, such as from a falling pound, as we’re seeing right now and could see a lot more of.

Then you apply the solution which is to remove those risks. That’s usually a forward contract to lock in the rate at which you can meet your required budget.